These are just my notes of the book Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, all the credit for book goes to the authors and other contributors. My solutions to the exercises are on this page. Additional concise notes for this chapter here. There is also a Deepmind's Youtube Lecture and slides for model free value estimation and model free control. Some other slides.

We do not know what the rules of the game are; all we are allowed to do is watch the playing. Of course if we are allowed to watch long enough we may catch on a few rules. - Richard Feynman

Introduction

Unlike previous chapter, we do not assume full knowledge of probability distributions of transitions, Monte Carlo methods only require experience - sample knowledge of states, actions and rewards. It can learn from actual experiences, despite having no prior knowledge of environments dynamics and from stimulated experience, although model is required it needs only the sample transitions.

The term "Monte Carlo" is often used more broadly for any estimation method whose operations involves a significant random component. Here we use it more specifically for methods based on averaging complete returns. This can be considered a bandit problem except that here all the bandits (states) are related. To handle the non-stationarity we adapt the idea of general policy iteration (GPI) as seen previously.

Monte Carlo methods are good for episodic tasks because they have a simple idea that value of anything is simply the returns that it gets, thus the episode must always end.

5.1 Monte Carlo Predictions

The value function stabilizes only when it is consistent with the current policy, and the policy stabilizes only when it is greedy with respect to the current value function. Thus both the processes stabilize only when a policy has been found which is greedy with respect to its own evaluation functions. This implies that Bellman optimality equation holds and thus that the policy and value function are optimal. In either case, the two processes together achieve the overall goal of optimality even though neither is attempting to achieve it directly.

The goal here is to learn value function for some policy from episodes of experience under

and instead of having an expected return we use empirical mean.

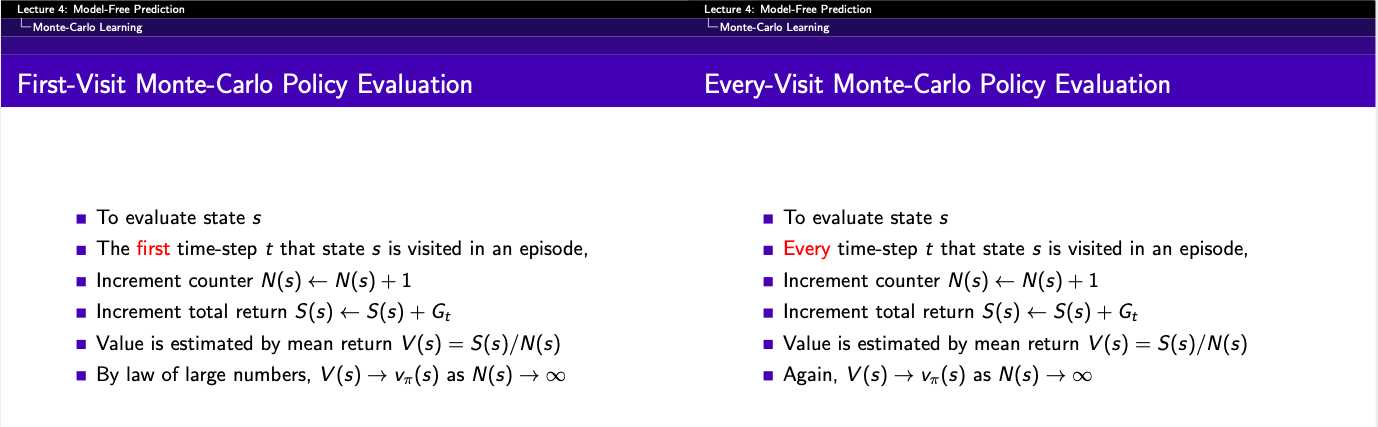

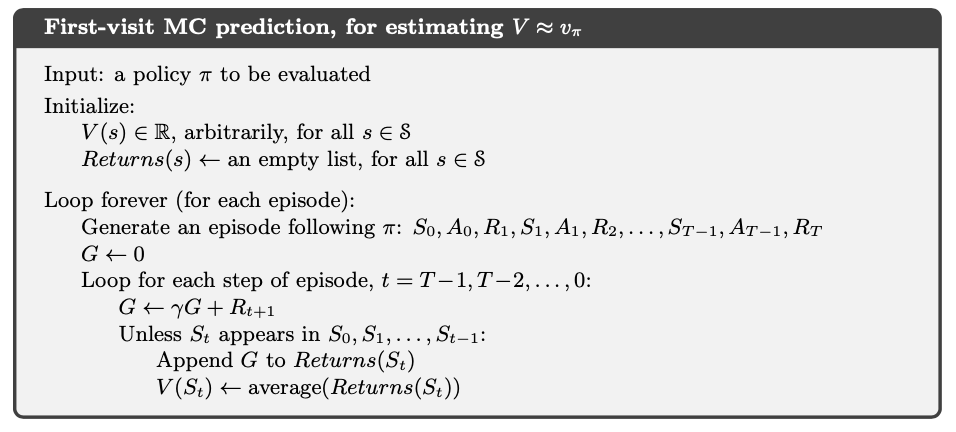

First visit MC only considers each state once in an episode and take mean from that point onwards we do not consider if in some loop we visit that state again. We get the optimal value function from the law of large numbers and keep on averaging them over multiple episodes. Every visit MC increments the state counter every time I visit that state and not only once per episode.

Note the subtle difference in the two

First Visit MC Process

We can perform incremental averaging which allows us to perform online learning. It basically means that "new me is old me plus some step size". We can write in in the iterative format as, for each state with return

Where (step-size) for stationary distribution and is some value for non-stationary distribution for running mean, i.e. forget old episodes so we don't have the baggage of past.

5.2 Monte Carlo Estimation of Action Values

When there is model available we can simply perform next state lookup and choose action that brings to state that has best value. However when there is not state value available then we must get estimates for action-value pairs, thus one of the primary goals of Monte Carlo estimation is to calculate . Just like for value estimation we can have first-visit MC and every-visit MC.

One serious problem we face is that there will be many state-action pairs that will never be visited and in order to compare we need to estimate the value of all possible actions in a state. One solution is to give each state a starting non-zero probability of being selected in the start. This guarantees that all state-action pairs will be visited an infinite number of times in the limit of infinite number of episodes. We call this assumption exploring starts.

5.3 Monte Carlo Control

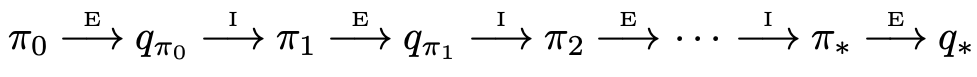

It follows the general principle laid in Policy Iteration where we loop evaluation followed by greedy policy but instead of having plain value function we have action-values.

instead of we have

Since no model is required we can make policy by simply taking argmax of action-values

We can use this as a guarantee to convergence as

But this assumes two things, one that episodes have exploring starts and other that we infinite number of episodes. To obtain a practical algorithm we'll have to remove both the assumptions.

There are two approaches for getting this working, first the vanilla approach. One is to hold firm to the idea of approximating in each policy evaluation. Measurements and assumptions are made to obtain bounds on the magnitude and probability error in the estimates, and then sufficient steps are taken during each policy evaluation. However, it is also to require far too many episodes to be useful in practice on any but the smallest problems.

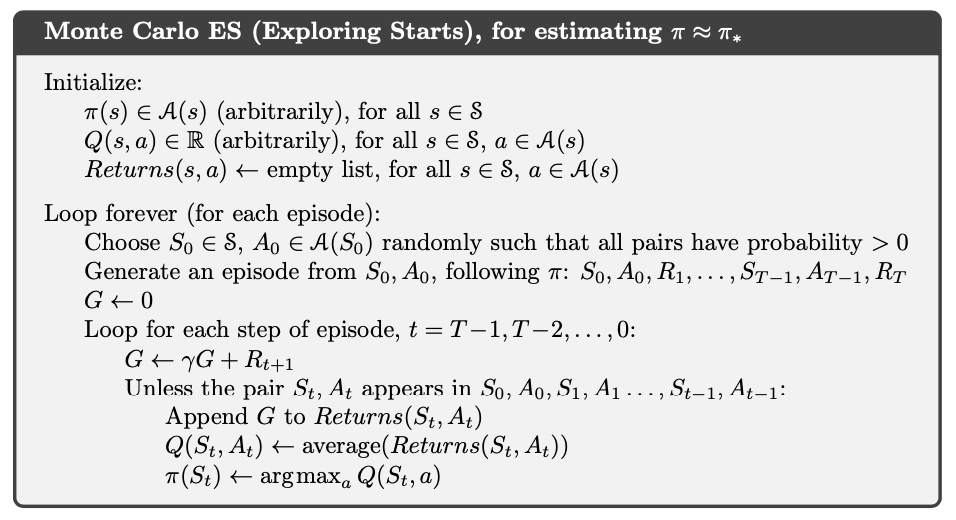

Monte Carlo ES (Exploring Start), for estimating . Note that this can be improved by having incremental averaging as here

It is easy to see that MCES cannot converge to a suboptimal policy. If it did, then the value function would eventually converge to the value function of that policy and that in turn would cause the policy to change. Though practically demonstrated, it has not been proven as a theory and is one of the most fundamental open theoretical questions in reinforcement learning.

5.4 Monte Carlo Control without Exploring Starts (On-Policy)

There are two approaches to ensuring this, resulting in what we call on-policy methods (evaluate or improve the policy that is used to make decisions) and off-policy methods (evaluate or improve a policy different from that used to generate data). Here we discuss the on-policy MC control w/o exploring starts.

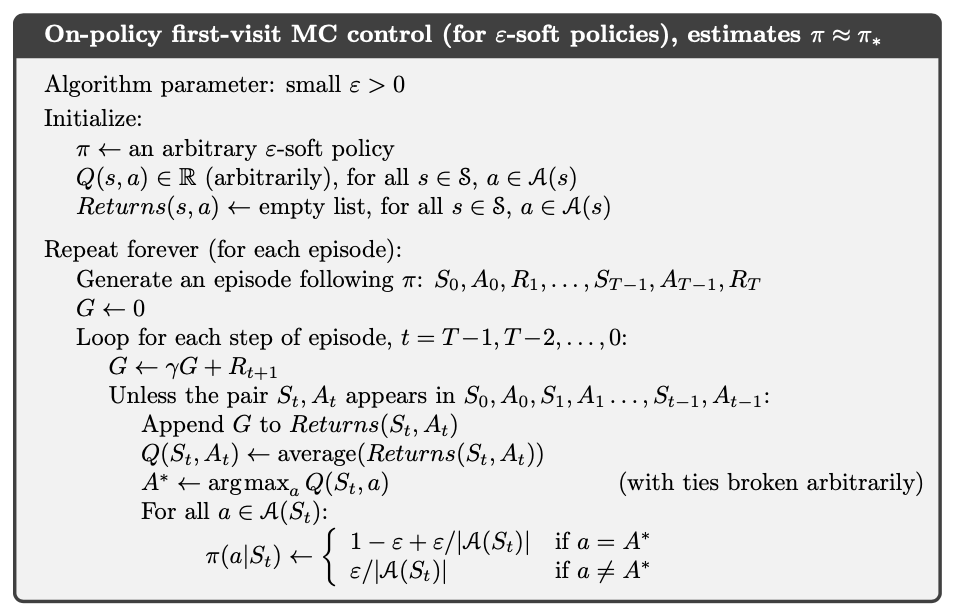

In on-policy control methods we have a soft policy, meaning that for all and all , but gradually shift to deterministic optimal policy. The on-policy algorithm that we chose here is -greedy that is it takes the maximal estimated action value but with probability they take a random action. We use a subset of -greedy called -soft in which the minimal probability of selection is and the remaining bulk of the probability is given to greedy action. Fortunately, GPI does not require that policy be taken all the way to greedy policy, only that it be moved toward a greedy policy.

On policy first-visit MC control (for -soft policies), estimates

We can show that -greedy w.r.t. to is an improvement over any -soft policy using the policy improvement theorem. Let be the -greedy policy as

The sum of a weighted average with non-negative weights summing 1 is less than equal to the largest number averaged. As we can also write it as and use this as averaging over all the actions

Thus by the policy improvement theorem, (i.e. for all )

If we now push this random action into environment we get the optimal policies as and then we can write as follows

We know from above that

The above two equations are same except that and if the two values are same then , i.e. we have reached the optimal policy.

Thus we have showed that there will be continual improvements in every step iff we already are not at the optimal value function. This brings us to roughly the same point as in the previous section only that we achieve best policy among -soft policies, but on the other hand we have eliminated the assumption of exploring starts.

5.5 Off-policy Prediction via Importance Sampling

All learning control methods face a dilemma: they seek to learn optimal action values conditional to subsequent optimal behaviour, but they need to behave non-optimally in order to explore all actions (to find optimal actions). The straightforward approach is to use two separate policies, one that the is learned about and that becomes the optimal policy, and one that is more exploratory and is used to generate behaviour. This is called off-policy learning.

Say that we want to calculate and and we have target policy and behaviour policy , where . In order to use episodes from to estimate values for , we require that every action taken under be occasionally taken under . This makes the deterministic and greedy according to the action-state value i.e. more optimal, while the behaviour policy remains stochastic in some states, more exploratory.

Almost all off-policy algorithms use importance sampling, which is used to estimate expected values under one distribution given samples from the another. Given a starting state , the probability of the subsequent state-action trajectory , occurring under policy

where is the state-transition function. Now we can calculate the importance sampling ratio as

Thus this is independent of the MDP and it's transition functions instead depends only on the two policies. Now we know to get the value for any state using policy we multiply the return by importance sampling ratio as

Now we are ready to perform MC algorithm that averages return from a batch of observed episodes following policy to estimate , again we can use both every-visit and first-visit MCE. We define the set of all time steps in which state is visited . For every-visit MCE it is convenient to have time series that cross the episode boundaries, so if state terminates at , next state will start from . For a first-visit, would only include time steps that were visits to in that episode.

Let denote the first time of termination following time , and denote the return after up through . Then are returns pertaining to state and are the corresponding importance sampling ratios. So we can calculate Ordinary Importance Sampling

and Weighted Importance Sampling as

or zero if the denominator is zero.

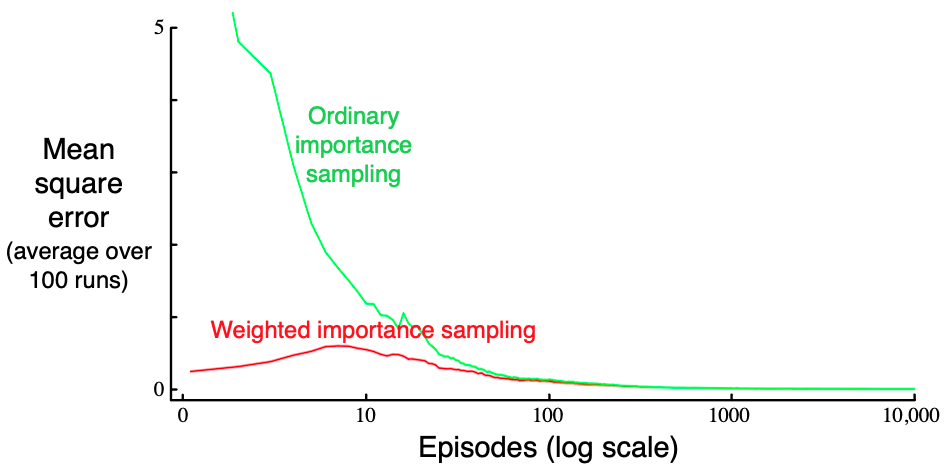

To better understand the difference assume that we run for just one step and calculate the value estimates. The weighted one will return same value as as terms cancel each other, in a way we call this bias. The ordinary will return the times the sampling ratio. Imagine that the sampling ratio was then the estimate would be ten times, which is far from actual sample. Thus we can summarise as follows "Ordinary has no bias but high variance and Weighted has bias but variance , though bias asymptotically reaches to zero".

In practice the weighted estimator has dramatically lower variance and is strongly preferred also every-visit algorithms are used because it removes the need to maintain which states have been visited.

Example 5.4 This question is used to evaluate this state: "the dealer is showing deuce, the sum of players card is 13, and the player has a usable ace (that is, the player holds an ace and a deuce, or equivalently three aces)". Using the target policy to only on or , ordinary and weighted value estimation over episodes is shown.

For example 5.4

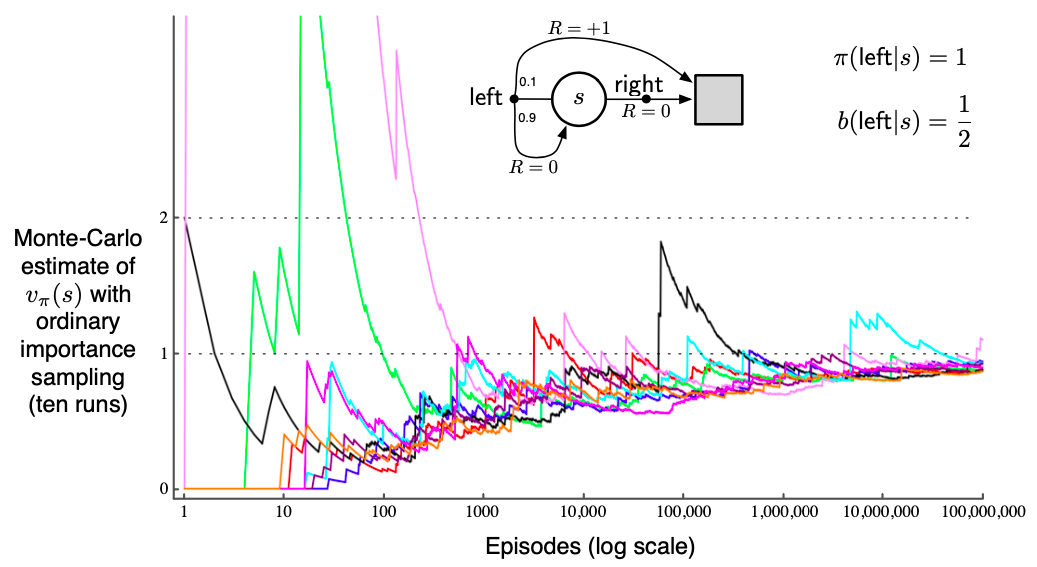

Example 5.5 Infinite Variance: since the target policy is and behaviour policy , the importance sampling ratio will be zero anytime takes a right. Thus weighted estimation calculates the estimation as as soon as takes left once.

For example 5.5

We know that variance , expanding it can say that if the mean is finite as is the case in above sample, the variance can be infinite only if expected value is infinite, in other terms when expectation of square of random variable is infinite. Thus we need to show that

So if we consider the MDP in the example we can calculate the mean as

5.6 Incremental Implementation

For derivation look here.

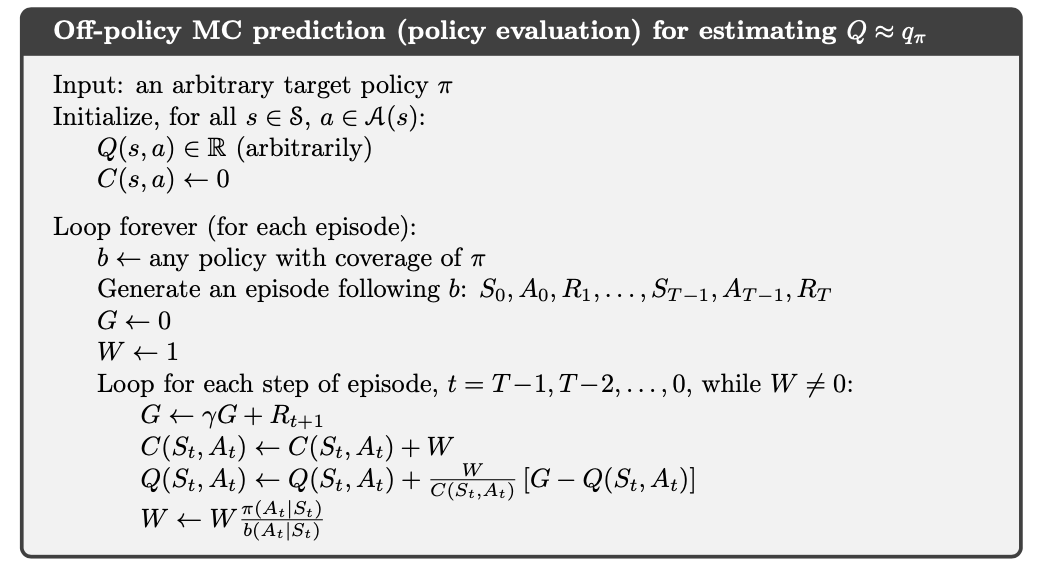

Off-policy MC Prediction (policy evaluation) for estimating

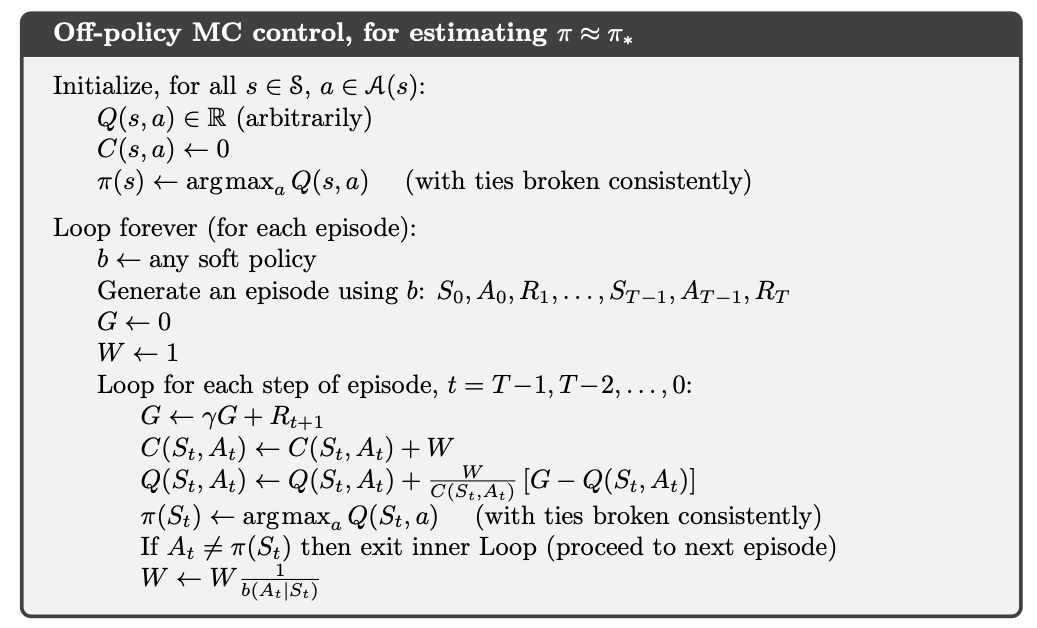

5.7 Off-policy MC Control

The behaviour policy can be anything, but in order to assure convergence of to the optimal policy an infinite number of returns must be obtained for all possible state-action pairs, which is achieved using -soft policy. A potential problem is that this method only learns from the tails of episodes, when all the remaining actions in the episode are greedy. If non-greedy actions are common, then learning will be slow, particularly states appearing in the early portions of long episodes. Potentially this could greatly slow learning.

Off-policy MC control for estimating