The biggest issue I find when learning AI is the lack of proper, well documented and most importantly simple code. Often the people who write these codes are professionals who spend most of their time writing industry grade software, but for people like me who don't have a lot of experience or practice with writing code and even less implementing research papers, this is a problem. Even the code that is available online doesn't properly explain the reason behind selecting a particular strategy, why one tensorflow function was used over the other, or which tensorflow function should be used here. Another problem, lack of computing power or data sets used by researchers, and even if somehow we are able to get those, how to actually use it! Well no more worries, I am here trying to solve this. In a previous blog post I wrote about the gist of this model. And here we finally tackle how to build this thing.

The first thing we need to know about this is way tensorflow works, since everything is the background and most of the python functions don't work, we need to figure out a way to use tensorflow functions to reach our goal.

You can find the actual code by clicking the link below:

yashbonde/transformer_network_tensorflow

Tensorflow implementation of transformer network

I recommend you open the code in one tab and read the reasons here, apparently you can't display blocks of same code on medium using github gist. Here I will discuss about specific code choices and explanation of some tricky parts. There is one major thing you need to know about, even if you have ignored that till now, using scopes, and using them well. The main reason behind having to use large number of scopes is because of the stacks of same units used in transformer network.

We start our process by writing down the outline of our transformer class.

class Transformer():

'''initialization code'''

def __init__(self, param):

# initialise parameters here

'''in-house functions - functions users should not call'''

def _masked_multihead_attention(self, args):

# code for masked multihead attention here

def _multihead_attention(self, args):

# code for multihead attention here

def _encoder(self, args):

# code to build the entire encoder here

def _decoder(self, args):

# code to build decoder

'''user callable functions - users can call if they want, but don't necessarily need to'''

def make_transformer(self):

# take the output of encoder and merge with decoder inputs

def make_loss(self):

# write the loss function and apply gradients functions

def initialize_network(self):

# initialize the session and variables

'''operation functions - functions to properly run the model'''

def run(self, args):

# code to run a single input sequence and generate outputs

# can use this function to both train and infer only

def save_model(self):

# save the model according to requirements

If you look at all the major functions used, they will be in this order. The way to write code for any model is in the template above. Divide the class in four major parts: initialisation, internal functions, user callable, operation.

Initialisation function has the def __init__() in it.

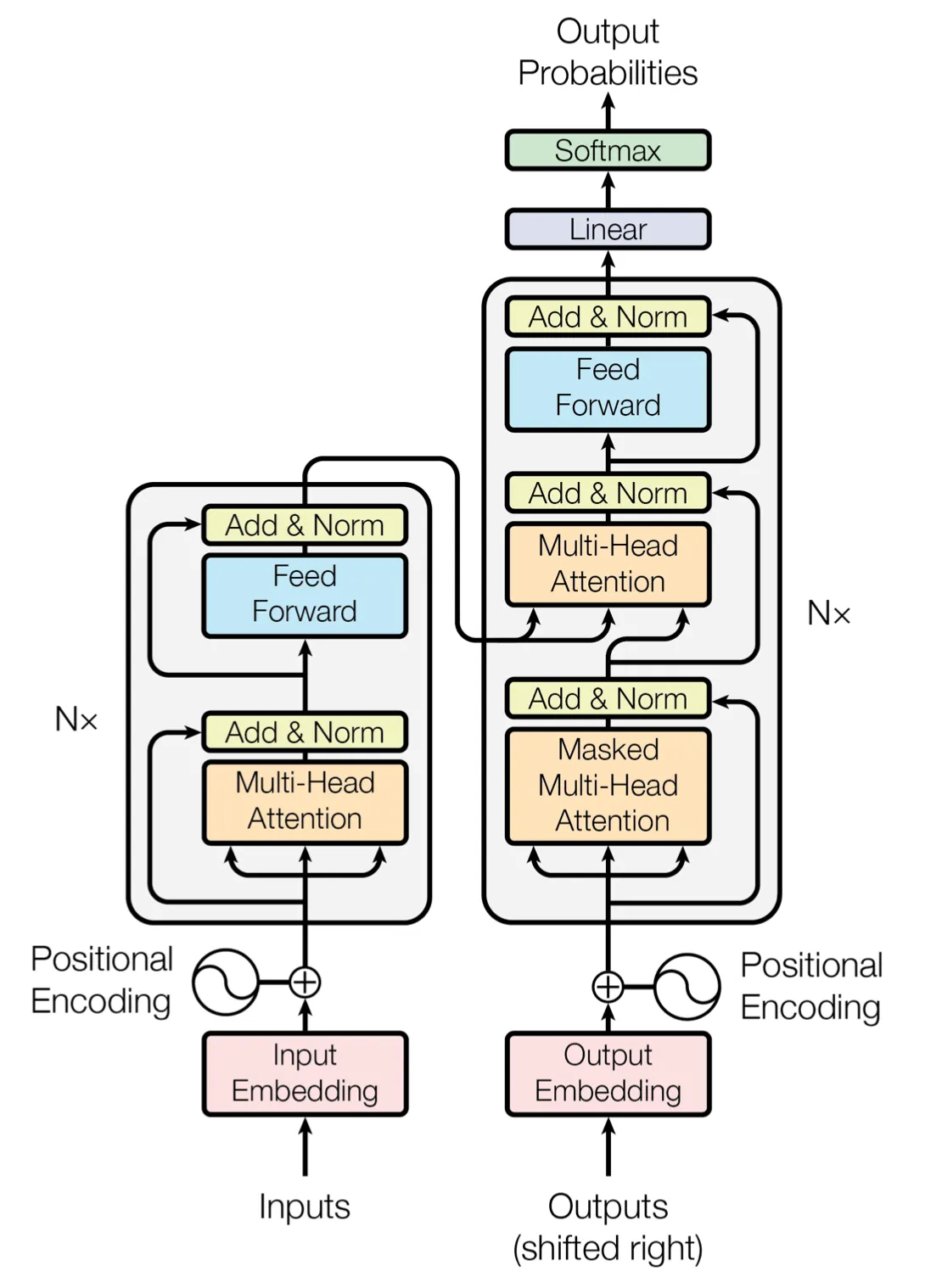

Internal functions has functions which are necessary to build the model. It has bulk of the code, since this is where all the operations are. In our code we have two major blocks masked-multihead-attention and multihead-attention, and two main units encoder and decoder. So we write functions for building those. Tensorflow backend operates as computation graph, thus this is where we write all the nodes to it. We denote these functions by placing underscore before their names.

User callable functions are the functions that user can call if they want, but don't necessarily need to, to run the model. Most of these functions will be called during __init__ only. In our case we have make_transformer() which combines the input from _encoder and _decoder to make the final computation graph which is able to perform inference. To make the model trainable we need to add more blocks, i.e. loss and training functions. We place these functions in make_loss() which gives the loss and train_step.

Operation functions has functions that the user calls as needed. For our code we have the run() function which runs a single iteration for an input sequence. You can also add code to save the model in any format that you want. The rule of thumb is that if the model is going to be improved in future save as a checkpoint file. If it's going to be deployed, use protobuf to store model as a frozen graph.

Almost every codebase can be broken down into these four blocks and then built according to this template. After countless days of writing code, both as a project and professionally, I personally made my own template and have been fine tuning it. You make one according to your own needs!

Initialisation Functions

So we start from the top, the first thing we define is the LOWEST_VAL which is the smallest value that can be used in the system. By default the lowest value that can be represented in a 32-bit float is ~ 1.175e-38. So we select a value that is closer to it, we selected 1e-36, as it is sufficiently smaller. We basically need to apply negative infinity, according to the paper, but since infinity values are not processed properly, we replace it with a very small number.

Next we import our dependencies, utils has function to determine positional encoding. numpy is our most important linear algebra library and tensorflow is used to make and process our model. Next we define our class and write initialisation values. Most of the values are pre-filled as per the paper, the only parameter we need is the VOCAB_SIZE which is the number of words in target language. We define some parameters like DIM_KEY and DIM_VALUE according to the formula given in paper.

Coming to line-52 I have defined masking matrix as a placeholder, so it can be changed or fed at run time. The main idea behind masking has already been explained in the previous blog post. Challenge is to implement it at the run time, when each input sentence might be of different length. At line-61 I define an embedding matrix, in case the user does not want to implement embedding for word beforehand.

Next we define four more placeholders, input_placeholder for the input sequence output_placeholder for the output sequence, labels_placeholder for the target label which is to be predicted and position which keeps track of the position till which the sentence has been generated. This last one is to use with the masking_matrix as an argument when using tf.nn.embedding_lookup(). Next functions are make_transformer(), build_loss() and initialize_network(). Use of these three will be explained later as we reach those functions.

[Masked] Multihead Attention

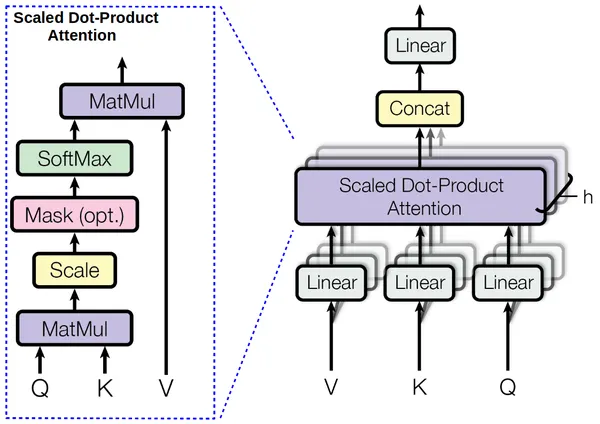

Shifting to the model architecture, if you think about it both the multihead attention are very complex and entities of their own, so we can convert them into functions, where they simply return the output tensor. This is what we have done by creating separate functions, though both can be converted into a single function. I just find having them as two different entities more convenient. At line-75 we start the multihead_attention() which takes four arguments, three of which are as explained previously and a reuse argument.

It is very important to use tensorflow functionality such as scopes very properly! This is the hidden trick that allows us to make these complex graphs possible. Scopes are nothing but the names given to the variables that are created, and in transformer we use stacks i.e. same variables are used multiple times. To use that we use function tf.variable_scope() to which we pass two arguments, the name of scope and whether to reuse it or not. The name of scope can be anything, it just tells that all the variables that are created under it will carry the name as <outer_scope> / <inner_scope> / <variable_name>. Also to note is that the first time we cannot pass reuse argument as true, since we have to define them first.

To store all the values of tensors that are created we make a list called head_tensors, as we define more and more tensors we will keep adding them into this list. We iterate over the number of heads that we have and just like outer scope, if reuse is not true it means we are creating these layers for the first time, we define reuse_linear as false. For each linear layer we define another variable scope. The best practice to generate variables under scope is to use tf.get_variable() function. The first argument will be the name and the second argument will be the shape. If we get the variable, we still need to initialise them, for now we use tf.truncated_normal_initializer which fills it with numbers present in truncated normal distribution.

This way we create the three weights, weight_q, weight_k and weight_v and perform further calculations to get the head. Once the head is calculated, we add it to the list containing the values of the different heads. After the linear layer iterations are finished, we now need to concatenate the values of outputs of different linear layers. We do that and perform the final linear operation, and return the value from multihead attention called mha_out.

In case of masked multihead attention we simply multiply another value (masking value) as shown in the diagram. To obtain that value we calculate it from masking_matrix that we had defined earlier. Now there is no way to just pass index and obtain the values in tensorflow. And implementing it by running a session and calculating those is a very slow and inefficient. But there is a workaround that, it involves using another tensorflow function called tf.nn.embedding_lookup(). It is logically similar to what we want, where we give it a matrix and list of indices that we want. This gives us the mask value, which we later multiply in the linear layers.

Encoder

Once done with the multihead attention rest of the code is quite easy to build. Here too we use variable scopes to keep track of variables that are being generated. We also make an empty list that we will populate with the outputs of each stack called stack_op_tensors. Next we iterate over the number of stacks that we have, if the we are at the first stack we need to give the input to model as input, otherwise we have to use the output of previous stack. Then we again open a variable scope and reuse them when needed. We get the output from multihead attention and perform further operations on it. For now I am using l2-normalisation, but feel free to use anyone that you think fits properly.

For each stack we have two sub-layers, the first one has multihead attention as described above and the second one has feed forward and normalisation part. After the calculation of each stack we add it to the stack_op_tensors and when finished with the number of stacks return the list containing the specific tensors.

Decoder

Decoder module is similar structually to encoder module except that each stack has three sublayers and inputs from encoder go in the middle sublayer. We again open up variable scope and reuse them when needed. After all the stacks are finished we get the final output and pass it through the dense layer to predict the final pre-softmax output.

User Callable Functions

I have three different user-callable functions, make_transformer() which defines the global scope and connect the output of encoder to the input of decoder and create global variable called decoder_op which will be used as prediction of the model. Next we use build_loss() which define the global loss and train_step which performs one iteration of gradient descent. I have done a change here, unlike the paper I won't decrease the learning rate manually, rather use AdamOptimizer to train the network.

The last user callable function is initialize_network() which does nothing but start a session and initialize variables by using global_variables_initializer().

Operation Functions

When making such large models it is important more than ever to be able to debug the code. The first thing we should be able to do is see all the trainable variables, so we make a function called get_variables() which returns all trainable_ops. And another one I am using is save_model() which saves the model in any format that you want. I am yet to finish writing that part, but there are a variety of formats that you can save your model in each with it's own unique advantage and disadvantages. Some popular formats are protobuf, frozen_graph, checkpoint files, servings, etc.

Now coming to the last function run(), it runs one iteration of input i.e. one iteration, length of output sequence long. The first major value that we make is the masking matrix, it is as described above a triangular matrix. If the user does not provide embeddings then we need to make our own. Using the common embedding matrix we get the embedding for text and then multiply it with the poisitional encoding we get from utils. We also make labels for that input sequence. If we are training argument is_training will be true, then we also need to keep track of the loss. So we define a variable called seq_loss which stores the value of loss incurred over the generation of sequence.

We iterate over the number of words we have to generate i.e. seqlen and run operations on it. If we are training the model then we need to run two more operations, one which calculates the loss and another to perform one iteration of training train_step. We return the generated sequence and if training the loss for generation of each word in sequence.

This model took me over three weeks to fully implement from scratch and was a great learning experience. I also trained the model on small toy dataset and made a jupyter notebook on it. Once the model is properly trained will link it here.