This is first in a series of blogs covering this project. TL;DR see this Github repo. Also for all you who do not understand the Indian number system just read this wiki. This is a follow up to my previous work where I train a language model on or moves and pose some questions.

If you have any freelancing work, contact me on my LinkedIn.

Initially this was going to be do and done kind of project but now it seems like this is going to take a while and if I am lucky I might just get a paper out of it. There are so many shitty papers out there that you can't believe something so meaningless can get a paper out. But anyways, it's them and we gotta do our योग. This blog is mostly a paper discussion and will be a quick one.

📶 What are power laws

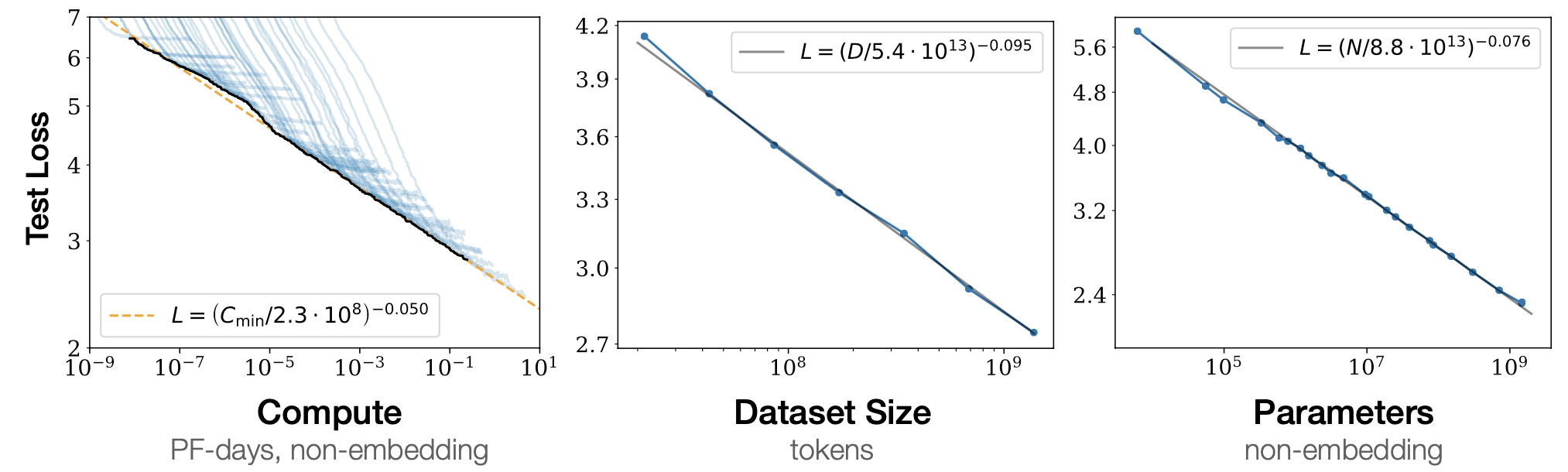

It used to be when compute was low that simply adding more layers to a network used to work. But this paradigm changed with very large model (GPT-2, BERT, T5, etc.) and with the investment in these softwares it became important to know how these model actually scale, what matters and what not. So OpenAI did a research and answered those questions based on Power Law. So we start our discussion with what is a powerlaw.

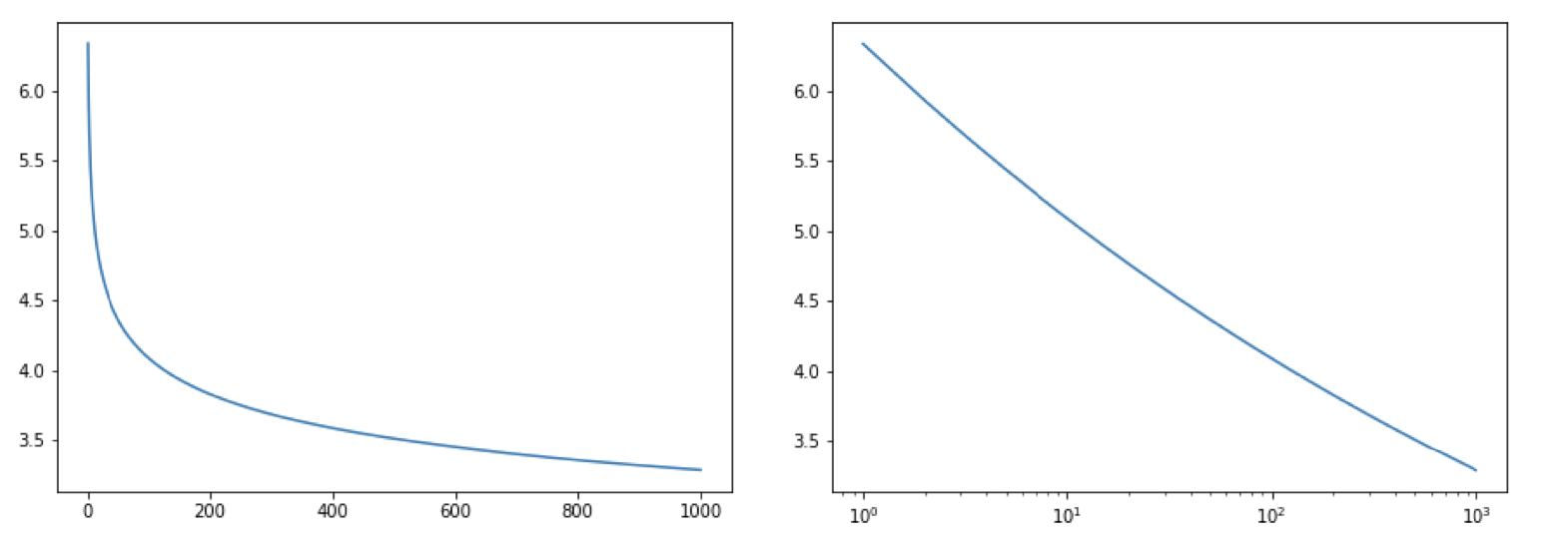

Powerlaws are mathematical relationship where changing one value causes a proportional change in the outcome or power law is a function where the value is proportional to some value of . Eg. doubling the length makes area times and volume times. So we can give it a form where and when considering volume . Such functions have three properties:

- Scale Invariance: given a relation scaling by a factor causes proportional scaling of the function itself ie. . Thus the log of these values gives a linear line.

- Lack of well defined average value, which makes it hard to apply traditional statistics like mean, etc. An example if the Pareto Distribution.

- Universality, which in gist means that as a different systems behave the same way. And the exponent in such a distribution () remains the same for those different system. In the paper it means that for a lot of different models the scaling parameters eg. remain the same for large number of values.

What are the lesson learnt, those with images are given below the bullet points:

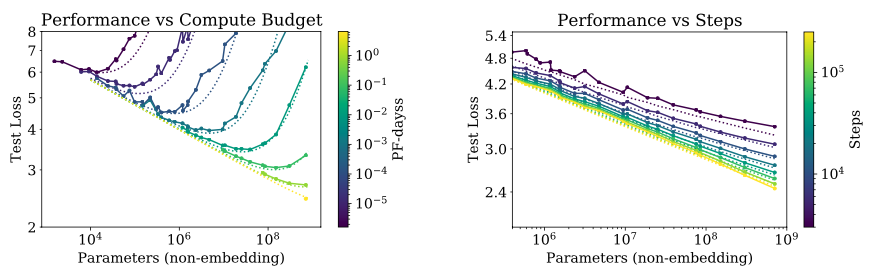

- Transformer performance depends very weakly on the shape parameters and when we hold the non-embedding parameters count fixed to .

- The variation in the loss with different random seeds is roughly , does this mean setting seeds during training is pretty much useless?

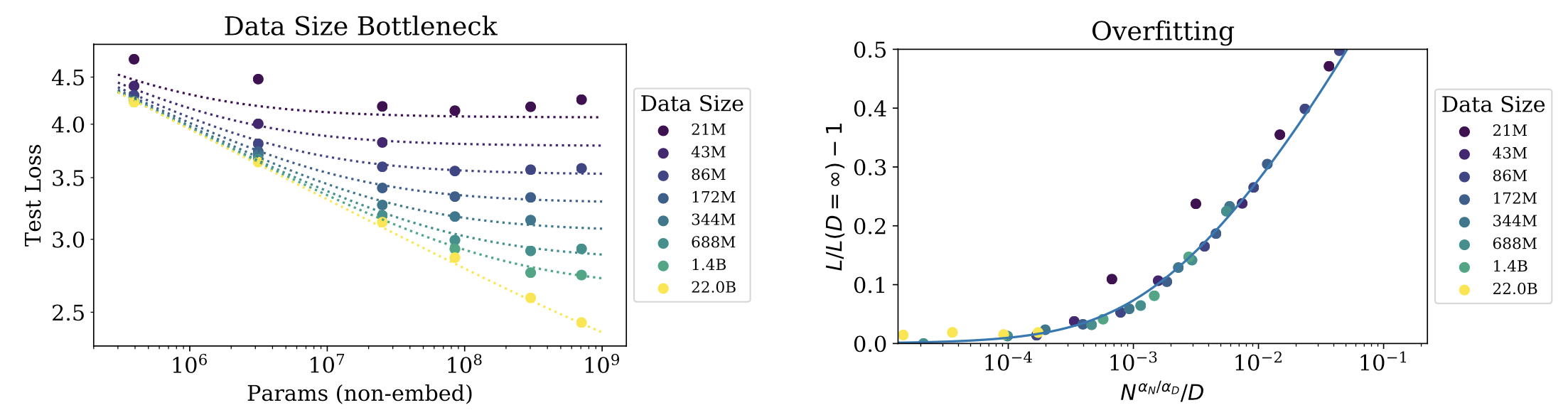

- To avoid overfitting when training within the above threshold of convergence we require . However, this according to my calculations actually comes .

- Convergence is inefficient: When working with a fixed compute but without any other restrictions on and , we attain optimal performance by training a very large network and stopping significantly before convergence. As given by relation

- The performance penalty depends predictably on the ratio , meaning that every time we increase the model size , we only need to increase the data by roughly to avoid a penalty.

- This is somewhat obvious but larger models are more sample efficient, reaching same performance with fewer parameters.

So what is the problem?

Kolmogorov defined the complexity of a string as the length of its shortest description on a universal Turing machine , .